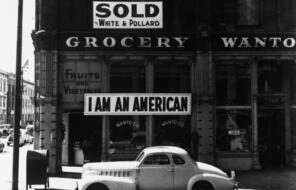

Supporting Question 3: Japanese American Resistance during WWII

Duration

Two 50-min class periodsSubject

- History

- Social Studies

Grade

9–12Language

English — USPublished

Get it in Google Drive!

Get everything you need including content from this page

Get it in Google Drive!

Get everything you need including content from this page

Overview

About This Lesson

Students learn about Japanese American resistance to incarceration. They conclude with a Formative Task that asks them to create a working definition of resistance based on information they learned about the resistance of Japanese Americans incarcerated during World War II.

Supporting Question

How did Japanese Americans resist their incarceration and assert their rights during World War II?

Formative Task

Students will create a working definition of resistance based on information they learned about the resistance of Japanese Americans incarcerated during World War II.

Resources in this Lesson

-

Facing History & Ourselves

-

Facing History & Ourselves

-

Facing History & Ourselves

-

Facing History & Ourselves

Lesson Plans

Day 1

Day 2

Formative Task

Unlimited Access to Learning. More Added Every Month.

Facing History & Ourselves is designed for educators who want to help students explore identity, think critically, grow emotionally, act ethically, and participate in civic life. It’s hard work, so we’ve developed some go-to professional learning opportunities to help you along the way.

Exploring ELA Text Selection with Julia Torres

On-Demand

Working for Justice, Equity and Civic Agency in Our Schools: A Conversation with Clint Smith

On-Demand

Centering Student Voices to Build Community and Agency

On-Demand