Japanese American Incarceration in WWII: A US History Inquiry

Resources

6Duration

Multiple weeksSubject

- History

- Social Studies

Grade

9–12Language

English — USPublished

Get it in Google Drive!

Get everything you need including content from this page

Get it in Google Drive!

Get everything you need including content from this page

Overview

About This Inquiry

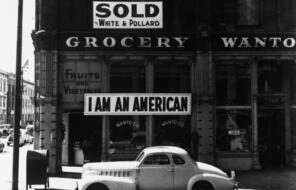

On December 7, 1941, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, the main American naval base in Hawaii. The next day, the United States entered World War II by declaring war on Japan. A few months later, the US government authorized the removal of all Japanese Americans from the West Coast—regardless of age or citizenship status. They were sent to prison camps surrounded by barbed wire and guarded by armed soldiers. Not one of them had been tried for a crime or even charged with wrongdoing. They were imprisoned solely because of their ancestry.

This C3-style inquiry guides teachers and students through an exploration of this history that engages the mind, heart, and conscience. By analyzing the conditions that led to the mass incarceration of Japanese Americans, students will gain a historical understanding of a period of prejudice and persecution, not just toward Japanese Americans but toward all people of Asian descent in the United States. Building on this knowledge, students will analyze sources that illuminate the experience of life inside the incarceration camps. They will also explore the various ways Japanese Americans challenged their imprisonment: through military service as well as protesting the draft, through the legal system, and inside the camps themselves. They will then explore the history behind the movement for reparations for incarcerees and their descendants.

Throughout the inquiry, students will reflect on the impact of this grave injustice—what many historians consider to be the nation’s worst wartime action and a violation of our nation’s highest ideals—on individuals and, more broadly, on American society. Students will also learn that Japanese Americans fought back against the injustice of incarceration. Guided by the essential question, “What can we learn from the stories of Japanese Americans who stood up for their democratic rights and freedoms during World War II?” students will consider how such acts of resistance forced the nation to live up to its own civic ideals and made significant contributions to the ongoing project of building and sustaining democracy in the United States. At the end of the inquiry, students will be equipped with the knowledge to connect this history to their own civic choices. Students will draw from their historical understanding, as well as their own agency and creativity, to explore how they might confront present-day injustices through informed action.

Compelling Question

What can we learn from the stories of Japanese Americans who stood up for their democratic rights and freedoms?

Supporting Questions

- What conditions made the incarceration of Japanese Americans possible during World War II?

- What was life like for Japanese Americans during incarceration?

- How did Japanese Americans resist their incarceration and assert their rights during World War II?

- How has the legacy of World War II Japanese American incarceration inspired activism among Japanese Americans today?

Learning Objectives

Students will be able to:

- Analyze the impact of the incarceration of Japanese Americans on individuals and American society.

- Consider how Japanese Americans resisted their own incarceration and made significant contributions to the ongoing project of building and sustaining democracy in the United States.

Preparing to Teach

Teaching Notes

Before teaching this lesson, please review the following information to help guide your preparation process.

Activities

Unlimited Access to Learning. More Added Every Month.

Facing History & Ourselves is designed for educators who want to help students explore identity, think critically, grow emotionally, act ethically, and participate in civic life. It’s hard work, so we’ve developed some go-to professional learning opportunities to help you along the way.

Exploring ELA Text Selection with Julia Torres

On-Demand

Working for Justice, Equity and Civic Agency in Our Schools: A Conversation with Clint Smith

On-Demand

Centering Student Voices to Build Community and Agency

On-Demand