Snapshots of Japanese American Incarceration

Get it in Google Drive!

Get everything you need including content from this page

Get it in Google Drive!

Get everything you need including content from this page

Residents of Japanese Ancestry Await Bus with Baggage

Residents of Japanese Ancestry Await Bus with Baggage

Image caption: San Francisco, California. With baggage stacked, residents of Japanese ancestry await bus at Wartime Civil Control Administration station, 2020 Van Ness Avenue, as part of the first group of 664 to be evacuated from San Francisco on April 6, 1942. Evacuees will be housed in War Relocation Authority centers for the duration. 1

- 1Photograph 210-G-A92, Records of the War Relocation Authority, Record Group 210; National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD, accessed September 20, 2023.

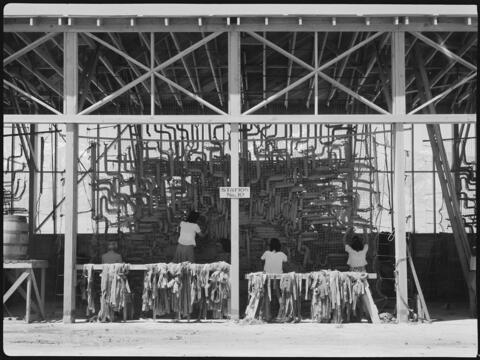

Japanese Americans making camouflage nets

Japanese Americans making camouflage nets

Image caption: Historian Erika Lee notes that the US government “aimed to create communities of inmates who . . . could be engaged in constructive work that would rehabilitate them as loyal Americans doing their part for the war effort. . . . Inmates could work in the camps, but their set wages of $12, $16, or $19 a month were far lower than what non-inmates were receiving. Such wages were also not enough to meet even minimal needs, like shoes and clothing, or to pay for such things as mortgage payments on property owned outside the camp.” 1

- 1Erika Lee, The Making of Asian America: A History (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2015), 237.

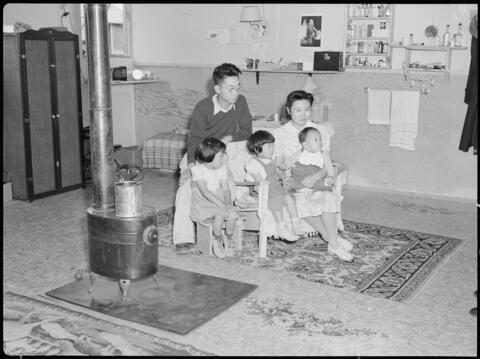

Family in their barrack apartment, Tule Lake Relocation Center, California

Family in their barrack apartment, Tule Lake Relocation Center, California

Image caption: Historian Erika Lee describes daily life for Japanese American incarcerees as “one of monotony, anxiety, and growing discontent,” but also notes that “inmates were enormously creative and tried to make homes out of the barren, desolate barracks.”

1

- 1Erika Lee, The Making of Asian America: A History (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2015), 237.

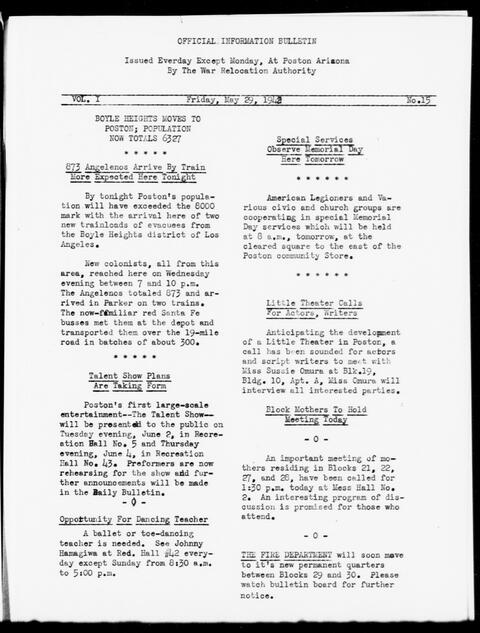

Official Information Bulletin

Official Information Bulletin

Image caption: Official information bulletin (Poston, Arizona), May 29, 1942. This is a news bulletin that was published by the Japanese Americans detained in Poston. It provides camp information from the current population of the camp as well as community needs and activities.

Woman making artificial flowers in the Art School

Woman making artificial flowers in the Art School

Image caption: A woman making artificial flowers in the Manzanar internment camp’s art school, Jun. 30, 1942, Manzanar, California.

Horse stalls converted into living quarters

Horse stalls converted into living quarters

Image caption: This center is a converted racetrack. Shown here are horse stalls that were remodeled into living quarters for families.

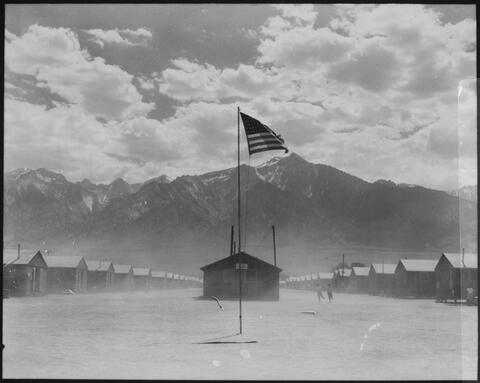

The Manzanar incarceration camp during a dust storm

The Manzanar incarceration camp during a dust storm

The nursery school at Tule Lake incarceration camp

The nursery school at Tule Lake incarceration camp

Image caption: Historian Erika Lee notes that “the camps offered nursery school, elementary school, high school, and adult education, but teachers were often few in number, overworked, or untrained. School facilities needed to be built and textbooks and other supplies were in short supply.” 1

- 1 Erika Lee, The Making of Asian America: A History (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2015), 237.

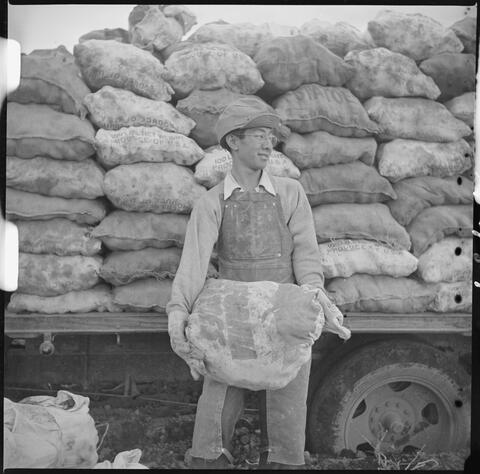

A worker loads potatoes grown on the farm of the Tule Lake incarceration camp

A worker loads potatoes grown on the farm of the Tule Lake incarceration camp

Image caption: By the fall of 1943, Tule Lake Segregation Center, north of Sacramento, became the largest ”city” in California, ballooning to nearly 19,000 people. . . . With a larger workforce, the administrators expanded the farm and expected a huge harvest, but the laborers complained of poor food rations and major safety concerns. Then a truck carrying Japanese American laborers from the farm had an accident. Nearly 30 workers were injured. One died.

Farmworkers refused to go back to work. “They recognized that they had leverage by having the strike right when the crops [were] ready to pick,” explained [author and actor] George Takei, a survivor of incarceration. “The camp director turned around and brought in Japanese Americans from other incarceration camps to break the strike.” 1

Help students analyze these images with the Analysis of Snapshots of Japanese American Incarceration and explore the lesson plan featuring these materials

- 1Lisa Morehouse, “Farming Behind Barbed Wire: Japanese-Americans Remember WWII Incarceration,” NPR, February 19, 2017.