Reimagining Home

Duration

Multiple weeksSubject

- English & Language Arts

Grade

11–12Language

English — USPublished

Get it in Google Drive!

Get everything you need including content from this page

Get it in Google Drive!

Get everything you need including content from this page

Overview

About This Text Set

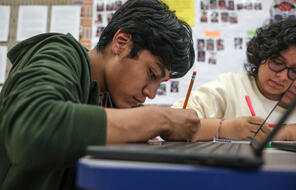

In this two-week ELA unit for grades 11 and 12, students investigate the many ways that people seek to define and discover the concept of home. The multi-genre text set showcases a range of voices reflecting on experiences of home through family, place, culture, community, nature, identity, and more. Students engage with these texts to reimagine “home” over the course of seven lesson plans, culminating in two summative assessment options.

Explore What It Means to Reimagine Home

The desire to establish a sense of home is deeply rooted in the human psyche. From ancient tales to modern narratives, this desire appears as a major literary theme, underscoring the human need for comfort, safety, identity, memory, and belonging. Yet the concept of home is expansive and ever-evolving. For some, home is indeed the place where we live, where we are born, or where we die. For others, it is something we do—music, art, athletics, writing—in tandem with who we are. Some find home in solitude, some find it in nature, and others find home in community or the people they love.

While the definition of “home” resists being pinned down, it is more than just a physical place; it is a psychological space, too. Between these spaces, we can reimagine “home” in ways that empower us to define how and where we belong in the world.

As older adolescents grapple with what it means to leave home, narratives focused on this universal theme become particularly resonant and relevant. Studying literature that explores and expands the possibilities of “home” can empower young adults as they prepare to enter a new or less familiar landscape.

Essential Question

How can reimagining “home” empower us to define how and where we belong in the world?

Preparing to Teach

Teaching Notes

Lesson Plans

Unlimited Access to Learning. More Added Every Month.

Facing History & Ourselves is designed for educators who want to help students explore identity, think critically, grow emotionally, act ethically, and participate in civic life. It’s hard work, so we’ve developed some go-to professional learning opportunities to help you along the way.

Exploring ELA Text Selection with Julia Torres

On-Demand

Working for Justice, Equity and Civic Agency in Our Schools: A Conversation with Clint Smith

On-Demand

Centering Student Voices to Build Community and Agency

On-Demand