A Part and Apart: Inclusion and Exclusion in Our Jewish Communities

Duration

Two 50-min class periodsSubject

- History

- Social Studies

Grade

6–8Language

English — USPublished

Overview

About This Lesson

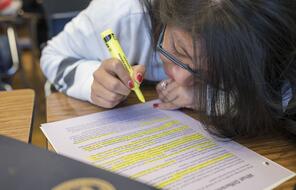

This is the third lesson in a three-lesson series highlighting the historical and contemporary experiences of Jews of Color, Sephardic Jews, and Mizrahi Jews while also considering the impact of exclusion, antisemitism, and racism on people who share these Jewish identities. This two-day lesson begins by using the story of Passover to examine how students define their own identities within the context of the Four Children. This exercise frames an exploration of how identity labels can be both beneficial and harmful, and provide a sense of belonging or a sense of exclusion. The lesson then narrows in focus to examine the Jewish identity label “Jews of Color.” Through survey data, personal testimonies, and artistic expressions, students learn about the experiences of Jews of Color, both within and outside of their Jewish communities, and consider how well their own communities strive to be inclusive spaces where diversity of Jewish identity is welcomed and represented.

This lesson was created in partnership with the Jewish Education Project in conjunction with the Shine A Light Initiative.

Preparing to Teach

A Note to Teachers

Before teaching this lesson, please review the following information to help guide your preparation process.

Lesson Plan

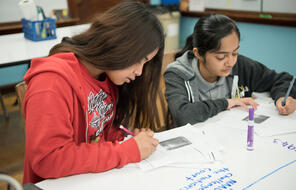

Day One: Labels That Help and Labels That Hurt

Day Two: A Part and Apart

Materials and Downloads

Quick Downloads

Get Files Via Google

Resources from Other Organizations

Additional Resources

Unlimited Access to Learning. More Added Every Month.

Facing History & Ourselves is designed for educators who want to help students explore identity, think critically, grow emotionally, act ethically, and participate in civic life. It’s hard work, so we’ve developed some go-to professional learning opportunities to help you along the way.

Exploring ELA Text Selection with Julia Torres

On-Demand

Working for Justice, Equity and Civic Agency in Our Schools: A Conversation with Clint Smith

On-Demand

Centering Student Voices to Build Community and Agency

On-Demand